An enemy who epitomizes Old School football perfectly

As a child, I hated the Green Bay Packers. Oh, I possessed an underlying sense of respect, even awe perhaps, for what they had accomplished (just starting my fb fandom right after their best successes). But reading about those narrow, breathtaking victories over the Dallas Cowboys--my team--created a resentment.

Over time, though, I've come to not only respect, but greatly admire Vince Lombardi and his boys, what they accomplished. Truly a powerful program, and they got the most out of their abilities, maybe more.

With that in mind, this column is a tribute to the "heart of the Packers," a guy who characterized lunch-pail, old school toughness and commitment as well as anyone ever could.

__________________________________________

A boy grows up in a rough Chicago neighborhood with no father figure and loses his mom at the turbulent age of 13. His life has been filled with confusion, anger, and an inner cold to match the “Windy City” winters. Does this future 6-3, 235 pound beast wander through a building-filled proverbial desert wreaking havoc?

According to Green Bay’s “Golden Boy” Paul Hornung, Ray Nitschke set on a path for the penitentiary his first pro seasons. With his frustrations boiling over on the bench, he longed to unleash his fury on the opposition. Not having an outlet, Nitschke began to strongly consider leaving the Packers and football altogether. Without a future on the gridiron, Hornung’s hunch might prove true.

According to Green Bay’s “Golden Boy” Paul Hornung, Ray Nitschke set on a path for the penitentiary his first pro seasons. With his frustrations boiling over on the bench, he longed to unleash his fury on the opposition. Not having an outlet, Nitschke began to strongly consider leaving the Packers and football altogether. Without a future on the gridiron, Hornung’s hunch might prove true. But with a new leader comes new opportunities for the forgotten. This head coach demanded players give all their guts for glory, accepting nothing less. Place Vince Lombardi in the role of mad scientist, and Ray Nitschke would be his perfect creation.

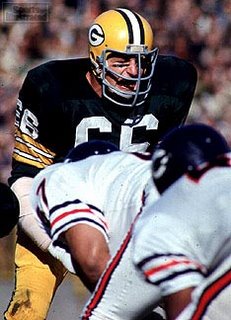

If you’ve seen Lombardi’s middle linebacker on the screen, you know the maniacal glare shouting through his helmet. His facemask becomes prison bars, and you’re not sure if he’s the villain opposing quarterbacks see or the hardened prison guard he played in the movie “The Longest Yard.”

Kansas City Chiefs’ Hall of Fame quarterback Len Dawson endured a much-too-close vantage point in the first Super Bowl. He recalls Nitschke “foaming at the mouth” and believing “This is the ugliest, meanest-looking person I’ve ever seen.” Opposing lineman Monte Stickles vividly recalled: “We had one or two fights nearly everytime we played each other. To me it was a challenge; to him it was war and destruction.”

Ray didn’t spare his teammates either. After all, practice should be prep time for that 60-minute weekend war in his way of thinking. Nitschke popped marquee Packers like quarterback Bart Starr or Paul Hornung with a Sunday vigor.

But he focused the bulk of his hatred on opponents, most notably the team he grew up wanting to play for—the Chicago Bears. Tight end Mike Ditka, the “Monsters of the Midway” version of Nitschke, recalls brutal dealings with the Hall of Fame middle linebacker. Ditka, as a rookie, used what Nitschke deemed “dirty tactics” in a pre-season game. Afterward in a Milwaukee bar, Ray challenged Mike face-to-face.

Though teammates prevented this particular collision, many others ensued in the following seasons. In a 1964 contest, a first quarter Nitschke hammer put Ditka out of the game. The Bears’ future Hall of Famer eventually found his way back on the field, but not without help. “I continued to play, said Ditka in “Mudbaths and Bloodbaths,” but I had no recollection of anything until I saw the films."

Ray could take the punishment as well.

He once stayed in a game after breaking his arm, only to be rewarded with a broken nose the same 60 minutes.

One season a constant cut from the center of his forehead caused blood to drip down over his face the entire game. The opposing quarterback would look across and see the menacing Nitschke, blood mixed with dirt and grass hauntingly behind his facemask.

While at the University of Illinois, his team squared off against Ohio State. You could play without a facemask and demonstrate your toughness. In this case, a guard took out his four front teeth on a kickoff. Ray describes it like this, "During a timeout, somebody shoved a wad of cotton in my mouth and I went on with the game, spitting blood all over the field."

One of the best (and most humorous) stories on Nitshcke came during a Packers’ training camp. With a storm approaching, he found shelter under a large scaffolding observation tower used by the coaches. A strong wind blew the tower down and onto him. Bedlam ensued and Vince Lombardi panicked over whom the storm had victimized—until another player answered “Nitschke.” Lombardi, knowing the “heart of the Packers” more than anyone, calmly returned to practice. With laughter, many players recall Ray hollering from under the debris in anger.

Nitschke, with his omnipresent number 66 jersey, prided himself on more than his perfected warrior side. Nitschke tenaciously studied opponents' tendencies, proudly stating “There wasn’t anything on the field they came out with I wasn’t prepared for.” Whether via the run or the pass (25 career interceptions), offenses found this “Route 66” highly hazardous.

Nitschke, with his omnipresent number 66 jersey, prided himself on more than his perfected warrior side. Nitschke tenaciously studied opponents' tendencies, proudly stating “There wasn’t anything on the field they came out with I wasn’t prepared for.” Whether via the run or the pass (25 career interceptions), offenses found this “Route 66” highly hazardous. Unlike the passer who notches huge numbers but crashes in key moments, Nitschke rose even above his all-pro level in big games.

During the 1965 championship game, he stalked the great Jim Brown across the field, holding him to 50 yards rushing. In a game-clinching moment, the Packers’ ‘backer plodded thirty yards through mud-blackened ice and lunged to break up a sure Brown touchdown reception, preserving Green Bay’s 23-12 triumph. The Cleveland Browns’ Hall of Fame back (many say the best runner ever) referred to Nitschke as “the soul of the Packers” and “as tough as anyone.”

In Super Bowl II—Lombardi’s last hurrah—Nitschke smothered Oakland’s power running game. He forebode Raiders’ disaster by violently flipping fullback Hewritt Dixon for a loss on the game’s first play. Final score: Green Bay 33-14.

In the minus-20-degree wind chill of Yankee Stadium versus Y. A. Tittle and the New York Giants, he recovered two frozen-field fumbles to key Green Bay’s 16-7 1962 NFL championship game victory. In winning the contest’s MVP award, he inspired young University of Illinois middle linebacker Dick Butkus to later exclaim: “I would have gladly served as the chauffeur for the sports car they gave him.”

Nitschke explained the importance of overcoming adversity. “Everybody can play in fifty degree weather, but can you play in a hundred degree weather? Can you play in a wind chill of fifty below? It's a test. It's a test of your character and your team's character, and you have to make adjustments. It’s like life, you know.”

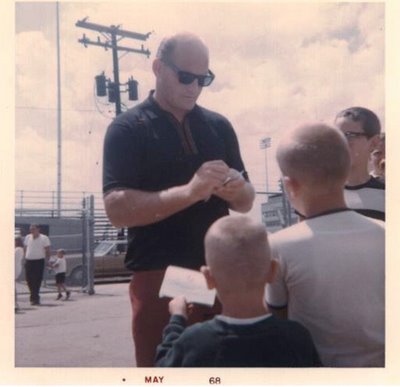

That life ended too soon from a heart attack at age 61, but Ray’s memories live much longer. He became a wonderful husband and father of three children; an off-the-field Ward Cleaver. Fans love him eternally. He always considered giving an autograph an honor and never charged for one. He relished the time to talk with such fans whenever possible. The state of Wisconsin even had a “Ray Nitschke Day” in honor of his retirement and Green Bay named a bridge after him.

Football fraternity brothers will miss Nitschke as well. During the Hall of Fame luncheons, he annually gave stirring speeches that emphasized the passion he felt toward the game of football. He considered playing such a game a privilege. Dan Dierdorf stated “he was like our heartbeat at those luncheons.” That special segment of the Hall of Fame weekend is now known as “The Ray Nitschke Memorial Luncheon.”

Unfortunately for opponents, Ray Nitschke released his massive hostility for fifteen seasons on the football field. Fortunately for family and fans, it was exceeded by his loyalty and love.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home